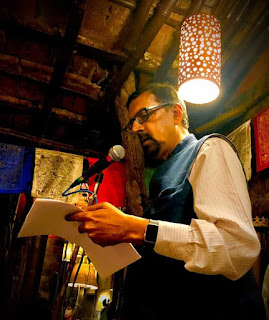

Interview with Lopa Banerjee

Today in Five Questions, we have Lopamudra Banerjee, translator of ‘Bakul Katha: Tale of the Emancipated Woman’ with us. She is an internationally acclaimed author, poet, translator, editor with seven books and four anthologies of fiction and poetry.

Santosh: A very warm welcome to you Lopa and hearty congratulations for yet another feather in your cap. Your passionate diligence is indeed awe-inspiring and inspirational. Three cheers again!

Let me begin with my first question:

“Writing my

own poetry and prose along with translating…has always been perceived by me as

both sides of a single coin.” You write thus in your translator’s note. I am keen to know whether the different layers, the myriad nuances, the shades of meanings hidden in various lines in poetry/prose/translation erupt from the subterranean depths of the same inner consciousness?

Lopamudra/Lopa

Banerjee: Hello Santosh Didi, at

the outset, let me tell you how honoured and humbled I am, that you chose to

interview me about my works of translation, and that itself is an unparalleled

joy to me.

In fact, yes, this

quote that I have mentioned in the opening line of my translator’s note in my

recent book of translation ‘Bakul Katha:

Tale of the Emancipated Woman,’ has its roots in the way my psyche as a

writer, poet, and lifelong learner of literature has been shaped in terms of

perceiving the various genres of literature that I have explored in my works as

of now.

To reiterate a bit about my writing journey (as I have already stated that in various other interviews of mine), I had started out as a journalist and feature writer covering stories on art, culture, and entertainment, literature, and humanities many years back, yet literature—poetry, short stories, novels were at the core of my consciousness as an immigrant writer and a woman living with her family in the US.

The mystic Sufi poet Rumi said: ‘Only from the heart can you touch the sky.’ The heart is the abode of our boundless possibilities, I strongly believe, and it is in the heart that poetry, prose, and other forms of literature and the arts reside and take shape in various manifestations. Every day, we grow with our poems, stories, our art, and become a small part of the collective consciousness of the universe, and it strengthens us from within in myriad unexplained ways. Hence, the various shades of meanings and nuances of the various literary texts I have read for a long time grew on me over the years, rooted to my inner consciousness, and from those subterranean depths, all the genres that I have explored in my writing have emerged, and spread their wings.

While the stint in journalism and content development taught me the restraint

and objectivity in expressing my thoughts on a particular subject, exploring

literary writing, poetry, prose, and translation have taught me the artistry of perceiving

the nuances of human life, the essence of my diasporic existence, with my roots

in India and my physical presence in the US. Both my

original writings and my literary translations spring out from the same quest.

Santosh: As we have co-edited many anthologies, I

know you as a very intense person, writing with an

emotional fervor that is often very palpable.

Translation, I know, is indeed a very humongous task, which can be undertaken

only by people who are focused, and passionate. When you are translating, there

is the danger that your own passion might get superimposed on those of the

characters, inadvertently. How do you steer clear of this danger?

Lopa: Santosh di, what you have asked me is already

stated by myself in my first full-length book of translation of Nobel laureate

of Bengal, Rabindranath Tagore’s work, ‘The

Broken Home and Other Stories.

“In spring 2015, I

felt an insatiable urge to translate into English the classic literary works

from my very own Bengali roots, which, at some point or the other, had

fascinated me, filled me with awe and inspiration. However, while the act was a

spontaneous outburst of my adrenaline rush, I also admit that I was intimidated

by the idea of executing it… As I trudged the road, I was apprehensive, lest my

effort of translation gets lost in the multitudes of voices already out there.

At the same time, I believed that my distinct emotional fervor and the honest

ingenuity would be the backbone of my attempts at translating the bard’s

literary masterpieces.”

As

a writer and translator, I have been trudging on a very difficult path, and

quite an emotionally taxing one too, which weighs on my sensibilities. As a

translator of literary classics, when I have undertaken the task of translating

a particular story of a novel, I have tried my best to depict the essence of the

characters’ journeys, the lyrical beauty of their portrayal as depicted by the

literary masters, their original creators, and in it, my passion as a

storyteller and poet will intrude only to the extent that it doesn’t mess with

the underlying essence, the message that the original author intended to leave

behind for his/her readers.

The readers of my books of translation have often remarked that they enjoy the

books that do not read like translations, which gives me the subtle message

that I can convey the essence of the original narratives.

Santosh: Yes,

you are right. Let me tell you Lopa, that you have succeeded

in conveying the essence of the original narratives remarkably well.

You have translated Bakul Katha, the third novel of the masterpiece

trilogy, so many years after it was first published in Bengali in the year

1974. How and why did you choose to translate this very novel from the widely

honored, acclaimed, Jnanpeeth Awardee [1976] Ashapurna Devi’s phenomenal literary

oeuvre?

Did you think that it would open new

vistas/windows/new manifestations resonate with contemporary women, making

them mull over the centennial patriarchal mindsets and its perpetuity or

whittling down?

Santosh: Yes, I have read that immensely erudite blurb of Dr. Sanjukta Dasgupta where she also mentions that the translator's engagement with the translated text is not just a labour of love, but "about bringing together in an immersive mode, the source text and the target text in a felicitous bonding."

Let me echo her words that you have been able to achieve that felicitous bonding extremely well.

Lopa: In the literary and academic culture that I grew up on (both Bengali as my mother tongue, and English as my acquired language), the significance of women’s voices was understood and internalized pretty early, since we were fed on a rich, diverse diet of the eminent feminist authors of the pre and post-independence days. Born in the latter half of the 1970s and carrying on with my literary studies from the 1990s and journeying with it for decades now, the edgy, volatile, and ever-evolving world of women, their sisterhood and travails, brought out with seamless flow in the fictional narratives of Ashapurna Debi, Mahasweta Debi, Pratibha Basu and later, Nabanita Dev Sen, Taslima Nasrin, Anita Agnihotri, and others have inspired me to explore the feminine subjectivity, the feminist ethos by delving into the female protagonists and trying to internalize their journeys.

Hence, translating Ashapurna Debi’s works came to me as a natural choice in a way. Her famed Satyabati trilogy, consisting of the travails of three generations of women, Satyabati, Subarnalata, and Bakul have intrigued me immensely, starting from my college days, and while talking to Ashapurna’s daughter-in-law, Dr. Nupur Gupta about getting the translation rights, it emerged that ‘Bakul Katha’, the last part of the trilogy had only been translated into Marathi, a regional language in India, while the two earlier novels of the trilogy, ‘Pratham Pratistruti’ and ‘Subarnalata’ had already been translated into English by eminent authors/translators.

With this backdrop, I undertook the task of translating this literary classic by Ashapurna into English, so that the global readers can now read the text and decipher the psyche of the author Ashapurna in depicting Bakul’s world, the women and men surrounding her amid the rapidly changing India of the 1970s.

In its essence, ‘Bakul Katha’ is the continuum of a

journey that started with Satyabati, Bakul’s maternal grandmother in the first

novel of the trilogy in pre-independence India, and with the depiction of

Subarnalata and her progeny Bakul, it is a journey of the diverse

manifestations of the emotional worlds of these women as they fight to attain

their rightful places in the universe. One who will read all these three novels

of the trilogy will eventually understand the evolution of Ashapurna’s psyche

in building the female protagonists. While in Satyabati and her daughter

Subarnalata’s world, the patriarchal shackles around them, the power struggles

around them, and their silent spirit of revolt define them, in Bakul Katha, the last novel of the

trilogy, she depicts the changing urban milieu of Bengal in the 1970s, a

post-independence world where the protagonist finds herself in a strange

intersection between hard-earned emancipation, the mindless abuse of freedom

and degeneration of values.

In its essence, ‘Bakul Katha’ is the continuum of a

journey that started with Satyabati, Bakul’s maternal grandmother in the first

novel of the trilogy in pre-independence India, and with the depiction of

Subarnalata and her progeny Bakul, it is a journey of the diverse

manifestations of the emotional worlds of these women as they fight to attain

their rightful places in the universe. One who will read all these three novels

of the trilogy will eventually understand the evolution of Ashapurna’s psyche

in building the female protagonists. While in Satyabati and her daughter

Subarnalata’s world, the patriarchal shackles around them, the power struggles

around them, and their silent spirit of revolt define them, in Bakul Katha, the last novel of the

trilogy, she depicts the changing urban milieu of Bengal in the 1970s, a

post-independence world where the protagonist finds herself in a strange

intersection between hard-earned emancipation, the mindless abuse of freedom

and degeneration of values.

Hence, I would strongly say that in ‘Bakul Katha’, the storyline will definitely resonate with contemporary women of the twenty-first century who are ever-evolving in their thoughts and actions, as they will mull over the nuanced representation of these women created by Ashapurna more than four decades ago. Most importantly, I strongly believe the book will compel them to think about the bygone generation of patriarchal values, and how the emancipation of women has been fraught with inner desires and aspirations, as the social fabric has kept changing with every generation.

Santosh: You are a poet, memoirist, fiction, non-fiction writer,

and translator. What do you like doing best? And yes tell me, while translating, how difficult was it to stick to the

original text and yet retain your creative touch?

Lopa: As a creative writer of all genres now, and

also as a writing mentor across the genres, I can only reiterate my belief that

literature has given us the ability

to extend the emotional landscape of our imaginations and touch

that sky with the might of our pen. Hence, there is no fixed answer to which

genre I prefer more over the other, it so happens that at a given time, I am

working on one particular genre, while at the back of my mind, the hunger to

explore other genres keeps rearing its head stronger every day. Also,

to my

understanding, the act of ‘dissent’ can happen with any art form whatsoever, be

it writing, singing, creating music, dancing, theater, or painting/sketching.

Apart from writing, I do enjoy teaching literature courses, dabbling in music,

theatre, and performing arts, and have also co-produced a poetry film ‘Kolkata

Cocktail’, and worked in it as a co-actor along with two other poets. Hence, the

hunger to explore various genres of art is strong within me, you can say, while

also the belief that there is enough fluidity between all these genres, as both

prose, poetry, theatre, music, and art have walked hand-in-hand, as I have drenched myself in the essence of these apparently

diverse forms. All of it forms the crust and core of my artistic consciousness.

In my literary

translations, starting from my translations of Tagore in ‘The Broken Home and

Other Stories’ and ‘Tales of Transformation: English translation of Tagore’s

Chitrangada and Chandalika’, to my recent translation of Ashapurna Debi, ‘Bakul

Katha: Tale of the Emancipated Woman’, my quest has been to recreate the world

of the original author and his/her creation, to delve into the psyche of the author

which brings the protagonists into life, while transcribing the details of that

world from the source language, to the target language, i.e., English. In doing

that, a subtle harmony, I believe, is necessary to seek a fine balance between

the authentic portrayal of the original text and the creative freedom in its

translation. While I have tried to carve this balance to the best of my

abilities, it is up to the readers and discerning critics to gauge if I have

been successful in my endeavour.

Santosh: When

your book was launched in an online event, I remember asking you a question as

one of the panelists, and which, if you permit, I would like to repeat. During

the discussion, you had said that while translating/transcreating, you had

found yourself amidst a sea of possibilities.

What were the dangers/possibilities lurking in that sea?

Did you ever have the fear of drowning in this sea?

While translating regional literature into English, there is always this fear or this consciousness in the mind of the translator: is it possible to transcribe the cadence, the musicality of the language in its translated form? Is it really possible to transfer the particulars of the oriental, vernacular cultural details to the western environment? Does that dilute the original flavour of the literary text while translating? Though that is a challenge that comes with every translation work, therein lies the joy of the creative process of translation.

Santosh: Very well-articulated, Lopa.

Before we draw the curtains, please tell us something about your next

translation project.

Lopa: While I am working on my original book manuscripts of poetry and short stories, I am also working on a few prestigious works of translation. My recent work-in-progress is the English translation of a novel/biography originally titled ‘Kobir Bouthan’ (Bengali) which is an award-winning research work by feminist author/poet of Bengal, Mallika Sengupta. The book focuses on the multifaceted history of the illustrious Jorasanko Thakurbari, Kolkata, the birthplace of Nobel laureate Tagore, and how the interpersonal relationships between men and women inside that mansion become historically significant in terms of gender and culture studies of the pre-independence era in India and also in terms of the development of Tagore’s poetic persona. Through this important translation work, which is a deeply layered narrative, I will try to unfold the subtle nuances of the socio-political history of Bengal in those times, while retaining the original flavor of the characters and the daily rigmarole of their lives.

Santosh: Let me stop here a moment and doff my hat to you for your diligence, single-minded concentration, and resilience. It is no mean feat! Let me confess, I could never have pulled off such a feat, and that too with such effortless ease.

Lopa: As a sensitive reader exposed to this rich literary world, I was not only intrigued by these classic masterpieces, but day after day, I kept feeling that as a translator, I could act as a cultural bridge, connecting the diverse trajectories of the poetic and fictional worlds of the vernacular authors' par excellence and the global readers who want to taste these intriguing narratives.

Wish me luck in moving forward in this exhilarating journey!

Santosh: All the best Lopa, may you touch greater heights with every passing day. It was indeed a pleasure talking to you.

Her poetry has been published on renowned platforms including ‘Life in Quarantine’, the Digital Humanities Archive of Stanford University. She has been a Featured Poet at Rice University, Houston in November 2019. Her recent publication is ‘Bakul Katha: Tale of the Emancipated Woman’, her English translation of Ashapurna Devi’s ‘Bakul Katha’, the final sequel of her Gyanpith award-winning trilogy novels ‘Pratham Pratisruti’ (The First Promise) and ‘Subarnalata’. Apart from writing and teaching, she has co-produced and acted in the critically acclaimed poetry film ‘Kolkata Cocktail’ (2019).

Excellent interview. Congratulations, Lopa and Santosh ma'am

ReplyDeleteThanks Vineetha Mekkoth

DeleteExcellent interview. Congratulations Lopa and Santosh Di

ReplyDeleteThanks Gauri Dixit

ReplyDeleteCongratulations Lopa and Santoshji.

ReplyDelete